Today – 21 March 2012 – is HUMAN RIGHTS DAY in South Africa…

and the 52nd. anniversary of the infamous ‘Sharpeville Massacre’.

Sadly for a great many of our people, it is simply another public holiday and has little or no meaning to them. To many others, they understand that it’s about equality of rights for all, but they don’t really understand the history behind it. Only the older generation really understand its significance.

Against this background – as well as my being a very amateur ‘historian’ – I thought it important for me to share, with readers here today, something of the human tragedy and the final triumphalism that this very special day in our national calendar represents, in terms of an event that has helped shaped modern South African democracy. As I understand it, anyway …

–

BACKGROUND

–

In 1952, the Nationalist government enacted new laws governing passes to be carried by blacks in South Africa.

Historically – as in most colonial states throughout Africa – there were laws that governed the movement of black people in areas and according to certain conditions. In SA, the earliest records show the Cape colonial government trying to keep black people out of the colony at the end of the 18th century.

The 1952 laws initially centred on all back males over the age of 16, with women’s passes being issued from 1954 onwards.

The ‘dompas’ (‘dumb pass’) was a document that detailed the personal history of the bearer and related movement and living restrictions – i.e. was employed by a white person and could be in a white business or residential area between certain hours, on certain days, under certain circumstances.

Failure to carry one’s dompas on one’s person – for whatever reason – 24/7 – was a criminal offence and arrest, jailing and even assault by police officers resulted. Repeat offenders were denied permission to remain in black township ghettos and banished to their traditional family homes in the deep rural areas, under future strict movement controls.

By 1956, widespread arrests of men and the new permit system for women (like an identity document) forced the women’s rights movement of SA (mainly led by the ANC Women’s League) to stage the now famous march on the Union Buildings in Pretoria on 09 August. This historic event is remembered annually in South Africa as a national holiday now – Womens Day.

–

THE PAN AFRICAN CONGRESS (PAC)

–

In early 1959, an Africanist group broke away from the African National Congress and, on 06 April 1959, at a conference attended by over 400 delegates from around South Africa, at the Orlando Community Hall in Johannesburg, the Pan African Congress was officially launched. Robert Sobukwe, a 34 year old lecturer in African studies at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, was elected its founding President.

The PAC promoted “multi-racialism” compared to the ANC which promoted “non-racialism” but both parties were strongly opposed to the pass laws.

In 1960, the PAC, being somewhat more radical and proactive compared to the ANC, decided to begin an anti-pass campaign starting on 21 March in Sharpeville, a black township of about 5000 homes near Vereeniging, south of Johannesburg. This community provided most of the workers to industry in that town and nearby Vanderbijlpark.

The idea was that blacks would not carry their pass that day and descend, en masse, on the local police station to present themselves for arrest, for violation of the laws. Sobukwe had written to the South African Police Commissioner a few days earlier, alerting him to their planned peaceful protests over a 5-day period commencing on the 21st.

–

SHARPEVILLE – 21 MARCH 1960

–

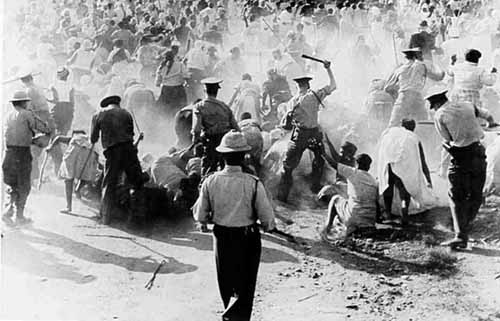

The police had got wind of the plans, since many people had already started the campaign the night before. As the crowds swelled to around 5000 people early on the morning of 21 March, the government sent in low-flying jets overhead to intimidate the marchers. As this had no effect whatsoever, they sent in armed reinforcements (about 130 officers) with armored vehicles to support the besieged men on duty.

By about 10h00, the estimated crowd was close to 20 000 people, all of whom were unarmed and singing liberation songs.

A police baton charge ensued and the command to open fire on the protesters was given.

–

At the end of the tragic melee, 69 people had been killed and, officially, over 180 injured.

More than 3 decades later, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission subsequently reported that injuries had been about 300 people and that a substantial number of those who lost their lives had been shot in the back, fleeing the bullets. (The police had argued that people started throwing stones at the police when the baton charge began and so the command to open fire was given.)

This was arguably “apartheid South Africa’s” darkest hour for human rights abuse.

–

LOCAL AND INTERNATIONAL OUTRAGE AT THE ‘MASSACRE’

–

Robert Sobukwe, who was by now lecturing at the University of the Witwatersrand, resigned that day, ensured his family were placed safely in ‘hiding’, and – with some committed others – started an early morning march on the Soweto police station, eight kilometres away. They were replicating Sharpeville, as were many other protesters at other police stations.

He and his cohorts were arrested and Sobukwe was sentenced to 3 years imprisonment. As tensions mounted, laws were changed and he subsequently was moved to Robben Island for a further 6 years. Thereafter, he was banished to house arrest in Kimberley – his hometown – were he sadly passed away from lung cancer in 1978.

The peoples’ outrage spread quickly around South Africa and – on the eve of government’s declaration of a national state of emergency on 30 March, the community buried their loved ones on 28 March in a mass funeral attended by thousands.

According to notes from the Nelson Mandela Foundation, “Nelson Mandela and his 29 co-accused in the infamous Treason Trial were still on trial when the massacre happened. In his autobiography, A Long Walk to Freedom, Nelson Mandela recalled: “The massacre at Sharpeville created a new situation in the country … A small group of us – Walter [Sisulu], Duma Nokwe, Joe Slovo and I – held an all-night meeting in Johannesburg to plan a response.

We knew we had to acknowledge the events in some way and give the people an outlet for their anger and grief. We conveyed our plans to Chief Luthuli, and he readily accepted them. On March 26, in Pretoria, the chief publicly burned his pass, calling on others to do the same. He announced a nationwide stay-at-home for March 28, a national Day of Mourning and protest for the atrocities at Sharpeville. In Orlando, Duma Nokwe and I then burned our passes before hundreds of people and dozens of press photographers.”

–

–

On 08 April, 1960, the ANC and PAC were officially banned in South Africa.

On 30 April, 1960, the United Nations Security Council passed the now famous Resolution 134 denouncing the government’s actions and calling for the abandonment of “apartheid” policies.

France and the United Kingdom abstained in that vote.

The mounting black anger in the country led to both the ANC and the PAC moving from policies of passive resistance to one of an “armed struggle” by the formation of military wings.

The “Sharpeville Massacre” was a catalyst for the Commwealth’s resolution to expel South Africa in 1961.

–

FAST FORWARD TO 1994 AND A NEW CONSTITUTION IN 1996

–

Almost three and a half decades after this tragic event, South Africa ushered in a new democratic order with the momentous national elections on 27 April 1994.

The new government immediately established 21 March as national holiday and named it Human Rights Day.

Speaking on 21 March 1996, President Mandela said:

“21 March is South African Human Rights Day.

It is a day which, more than many others, captures the essence of the struggle of the South African people and the soul of our non-racial democracy.

March 21 is the day on which we remember and sing praises to those who perished in the name of democracy and human dignity.

It is also a day on which we reflect and assess the progress we are making in enshrining basic human rights and values.”

On 10 December that year, President Mandela symbolically signed the country’s new democratic constitution into law in Sharpeville, flanked by Cyril Ramaphosa, who had led the ANC’s constitutional negotiating team, and Roelf Meyer, the team-leader of the former Nationalist government.

–

Copyright – The Sowetan – 1996

In his speech that day, President Mandela said the following:

“Out of the many Sharpevilles which haunt our history was born the unshakeable determination that respect for human life, liberty and well-being must be enshrined as rights beyond the power of any force to diminish.

These principles were proclaimed wherever people resisted dispossession; defied unjust laws or protested against inequality. They were shared by all who hated oppression, from whomsoever it came and to whomsoever it was meted.

They guided the negotiations in which our nation turned its back on conflict and division.

They were affirmed by our people in all their millions in our country’s first democratic elections.

Now, at last, they are embodied in the highest law of our rainbow nation.

This we owe to many who suffered and sacrificed for justice and freedom.

Today we cross a critical threshold.

Let us now, drawing strength from the unity which we have forged, together grasp the opportunities and realise the vision enshrined in this constitution.

Let us give practical recognition to the injustices of the past, by building a future based on equality and social justice.

Let us nurture our national unity by recognising, with respect and joy, the languages, cultures and religions of South Africa in all their diversity.

Let tolerance for one another’s views create the peaceful conditions which give space for the best in all of us to find expression and to flourish.

Above all, let us work together in striving to banish homelessness; illiteracy; hunger and disease.

In all sectors of our society – workers and employers; government and civil society; people of all religions; teachers and students; in our cities, towns and rural areas, from north to south and east to west – let us join hands for peace and prosperity.

In so doing we will redeem the faith which fired those whose blood drenched the soil of Sharpeville and elsewhere in our country and beyond.

Today we humbly pay tribute to them in a special way. This is a monument to their heroism.”

–

Brian Sandberg

Durban. South Africa.

————————–

POST-SCRIPT : 21 March 2013

John Robbie – a well known SA radio-journalist is at the site in Sharpeville right now, and has tweeted the following pics:

– The infamous police station, as it still stands today –

–

The old police station at Sharpeville http://t.co/69PHt4d598—

John Robbie (@702JohnRobbie) March 21, 2013

–

– The Garden of Rememberance, unveiled in 2002 –

–

The Garden of Remembrance at Sharpville. http://t.co/JoG5OALjJa—

John Robbie (@702JohnRobbie) March 21, 2013

–

– The memorial headstone at the epicentre of the garden and the arch –

–

The story of Sharpeville, marking the spot where the shootings happened. http://t.co/ugevqzXuKe—

John Robbie (@702JohnRobbie) March 21, 2013

–

Brian